Chandigarh is India’s only planned city; and at 60 years old, it is one of its youngest. After the trauma of Partition in 1947 and the loss of Punjab’s capital city Lahore to Pakistan, plans began by Prime Minister Nehru to create a capital city that would serve both states of Punjab and Haryana.

Work began in 1949 and finished in 1960. Over 50 small villages were cleared to create a city and union territory that Nehru claimed would be “symbolic of India’s freedom.”

After early plans by architects Mayer and Nowicki were scrapped, Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier was hired to implement Nehru’s vision.

Part of the City Beautiful movement, the goal of Chandigarh was to create a city unlike any other in India.

Billed as being one of the cleanest cities in India, as well as one of the wealthiest, we were keen to see how it differed from the many faces of urban India we had already experienced. “Sweeping boulevards, lakes, gardens and grand civic buildings.” Sounds lovely. “Buildings executed in Le Corbusier’s favourite material: reinforced concrete.” Hmm… not sounding so cozy. Maybe a little grey.

Le Corbusier’s urban plan was to create rectangular Sectors – each measuring 800 by 1200 metres; with each one intended to be self-sufficient and fulfill four functions: Living, Working, Circulation and Care of Body & Spirit.

Each Sector includes greenspace and small interior roads, with the main arterial roads dividing the Sectors and punctuated with roundabouts. The main arterial roads also feature tree-lined boulevards, to soften the effect and provide safe walking paths.

A quote from Le Corbusier, to describe his philosophy:

The curve is ruinous, difficult and dangerous. It is a paralyzing thing. The straight line enters into all human history, into all human aim, into every human act.

So how has this experiment worked? We don’t know how it functions for residents, but as tourists, we found the city design extremely disorienting. Yes, we could leave our hotel (in Sector 35), and walk down the street to discover stores and restaurants. We could walk on a sidewalk, and not have to dodge cars, scooters, and cow patties.

But where was the life? We trudged along in a straight line (sorry, Le Corbusier, most people do not follow a straight line – either in life or out for a stroll.) to our restaurant, then walked in a straight line back to our hotel.

We were “contained” in our self-sufficient Sector, until we hailed a tuk-tuk to take us to other Sectors. Driving along the arterial roads, the scenery remains unchanged from one Sector to the next – broad boulevards, trees and vehicles.

What lies behind those high walls?

Le Corbusier envisioned apartment buildings and office buildings designed in the same linear fashion as the Sectors – concrete, rectangular and efficient.

The main shopping area is Sector 17, also referred to as City Centre. We headed there with hopes of finding a “downtown” or a gathering place, and we did find a semblance of a centre core. Much of the main area is pedestrian-only, which is what every good city should have. The challenge is that there is no obvious centre – no collection of temples, churches, plazas or seating.

This pathway leads through a park to the main shopping area.

The shopping area runs for a number of blocks, with mid-range North American stores such as Nautica and Gant side-by-side with university bookstores and sari shops. It resembles North American plazas from the 60s – the same charmless layout and gone-to-seed ambiance. No-one can be bothered to even sweep the streets, it seems – it just ain’t as pretty as it used to be.

Still, parts of the shopping complex attracts greater crowds – drawn by the fake Ray-Bans and the cotton candy.

The shoeshine boys were hopeful – many of them chased us to demonstrate “a free sample of my work”. We probably should have taken them up on their offer, just to see what magic they could work with our worn-out Merrill running shoes and dirty old Birkenstocks.

One nice feature was this Le Corbusier-inspired “Open Hand” fountain. There are many Open Hand sculptures around the city – designed as “open to give, open to receive.”

Behind the fountain you can see the typical storefronts, not just in Sector 17, but throughout the city. Three-storey rectangles of stained grey concrete, plastered in signs for travel agents, shoe stores and hair salons.

After failing to make a connection to the City Centre, and trying to find the essence of Chandigarh, we headed over to Sector 10 to take in a couple of museums.

We spent a few hours wandering through the Government Museum and Art Gallery, admiring carvings, textiles, old terra cotta, Mughal miniatures, and a decent contemporary art section.

Le Corbusier – designed building.

The entrance.

We were keen to see some examples of Indian contemporary artists and these were a few of my favourites.

Sheltered Woman by Arpana Caur – an artist who works in feminist themes.

On the Beach by Amrita Sher-Gill. A fascinating Hungarian-Indo artist who lived a short, scandalous life and died tragically at age 28 under mysterious circumstances.

The Pilgrim – Guru Nanak by Jaswant Singh. I couldn’t find a lot about this artist, but his subject, Guru Nanak, is the founder of Sikhism.

Enroute to the museum, we walked through the Rose Garden, dutifully obeying the many “Keep off the Grass” signs, although very few other people paid attention.

There are many parks in Chandigarh, but they’re not at their peak – they’re dry and washed-out looking – the way our gardens look by late August. They must be stunning about a month after monsoon season.

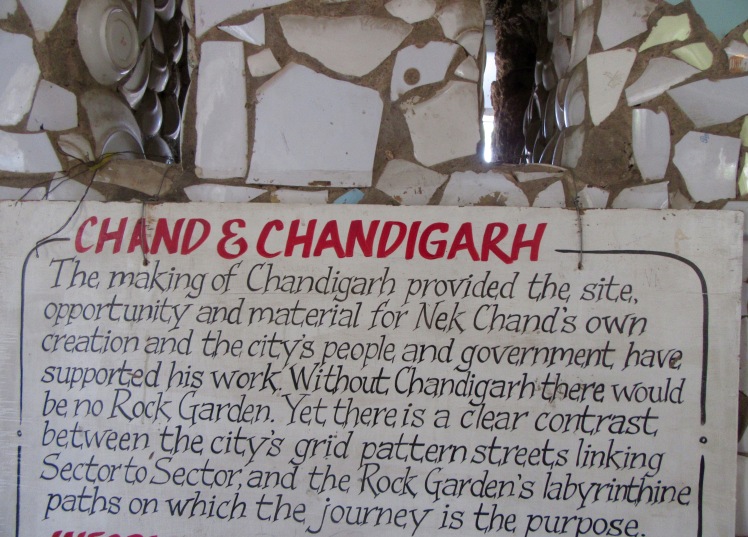

The Nek Chand Rock Garden is the one that draws the crowds. In absolute contrast to Le Corbusier’s straight-line world, Nek Chand is all about the curves.

With the idea that it is better to ask forgiveness than permission, Nek Chand worked quietly to create his fantasy garden, built of stone, debris, and discarded junk. The transport official began his work in 1957, and it took over 20 years to complete. At first, he worked in total secrecy at night for fear of being discovered. When authorities did find out what he was up to, they threatened to demolish it, but in the end decided the garden had civic merit and paid him a salary as well as provided money to hire other workers.

Today, it stands on 25 acres and is a fantastical creation of waterfalls, amphitheatres, narrow pathways, child-sized doorways, mosaics and 2000 sculptures.

Nature is well-incorporated into the stone and rock.

One of the many waterfalls provided a natural backdrop for photos.

Another small shaded pathway.

This gentleman came over to chat with us and find out what country we’re from. This has been a common experience here in Punjab, since so many Indians from this region either have family in the Vancouver area, or they have moved there themselves and are back in India for a holiday. It has provided an instant bond; followed by their curiosity about our impressions of India. Followed by photos of us standing beside them!

As it turns out, this gentleman and his wife have lived in Paris for 20 years, but their son has just graduated from University and is moving to Montreal.

Much of Nek Chand’s genius involved the creation of small “villages” of human and animal sculptures.

Look closely and you will see that these women’s bodies are encircled with broken plastic bangles.

There is a more sombre tone to this group – bent postures and sad expressions.

In the background, a wall made of broken crockery. In the foreground, some unsettling images. Are the figures begging? Holding out a plate for food perhaps?

The Nek Chand Rock Garden was our favourite part of Chandigarh. We walked with groups of people and had the opportunity to connect with them – for photos, for chats, or just for acknowledging curious stares with a smile.

We admired the unimaginable work that went into the making of this garden and wondered about the motivations of the artist. We cooled off in shady rest spots and shared benches with other tourists.

Best part of all – we all flowed together down the curvy, labyrinthine pathways – not a straight line to be found.

We’re happy to have had the chance to visit this unique planned city, and it was a welcome change to dial back a bit on India’s usually full-on assault, but still…

From a tourist perspective, there’s no heart, no soul, no people-watching and way too much concrete.

And now, we’re on our way to the foothills of the Himalayas – to Shimla, one of the British hill stations. We’ll be there for a week – enjoying day trekking in cool mountain air before we fly home from Delhi on April 8.

See you again in a few days.

Is this the end of your trip? What an adventure. You both look like pro travellers. Not sure this last stop would have been the highlight but certainly different. Looked relatively clean. We are enjoying Hoi An but being total slobs. Exclusively R and R! Not doing it justice probably.

Joan

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is nothing wrong with being in a lovely place and just doing very little. One of the best articles I read about Hanoi was to have a “do-nothing” day – just grab a Vietnamese coffee and people-watch in the park. We did that a few times.

Now we are in Shimla, taking full advantage of “doing very little.”

have fun!

LikeLike

Oops I see you Have said what your plan is. Just reread. Me

LikeLike

From your pictures, I would have to agree with you that the planned city of Chandigarh appears soulless. Not so, Nek Chand’s fantasy garden. I loved it – what a contrast to the rest of the city!

LikeLike

I’d be curious to visit other planned cities and see if any of them work better. It must be a tough job, being an urban planner – human beings have a great knack of messing up the best-laid plans.

LikeLike

It’s a treat to see Chandigarh, a place we didn’t get to when we were in India, however we lived for several years in La Chaux-de-Fonds in Switzerland, the birthplace of Charles-Edouard Jeannerret, Le Corbu, as he’s known. He’s either loved or loathed. For a total contrast to his philosophy check-out (Friedensreich) Hundertwasser, an Austrian artist/architect who believed that straight angles were an aberration. He said, “Just carrying a ruler with you in your pocket should be forbidden, at least on a moral basis. … The ruler is the symptom of the new disease, disintegration of our civilization.”

http://www.touropia.com/hundertwasser-architecture/

LikeLike

Wow – thanks so much for sending this link to Hundertwasser – my eye is so drawn to most of his work. I can’t imagine the engineering that must be involved in some of his creations.

Also – I subscribed to touropia – more travel inspiration!

I’m guessing Le Corbu has had some influence on La Chaux-de-Fonds?

LikeLike